AI gets a lot of attention today. Almost everyone has used it in one way or another. But there’s a difference between using an AI product and building one.

Not enough attention is given to turning these tools into useful features for real users.

In this post, I won’t explain what agentic AI is. I’ll show you how to build one.

The Goal

The goal is to showcase how implementing an agentic workflow into a business model can enhance it. The agent will be able to:

- Query data — Look up customers, orders, complaints

- Take actions — Update order status, process refunds, escalate issues

- Reference policies — Use RAG to look up refund rules and FAQs (RAG will be covered in a separate post)

This enables users to get insights from the platform that aren’t necessarily custom-built features. The nature of AI agents allows them to combine different data in ways that would otherwise require dedicated development effort.

We achieve this by providing the AI with tools to work with.

What Are Tools?

Tools are how an agent interacts with the world. Without tools, an LLM can only generate text. With tools, it can:

- Query databases

- Call APIs

- Send emails

- Update records

- Anything you define

A tool is just a function with:

- A name

- A description (tells the LLM when to use it)

- Parameters with types (tells the LLM what to pass)

- Logic that does something

The LLM reads the tool definitions and decides which ones to call based on the user’s request.

💡 Good descriptions and type hints matter. They ground the model and prevent hallucination.

Simulating a Business

It’s meaningless to create an agentic workflow without a core business model to work with. For this project, I simulated a food delivery platform where users can order food from various brands and restaurants, and file complaints about their orders if there are issues.

The Domain

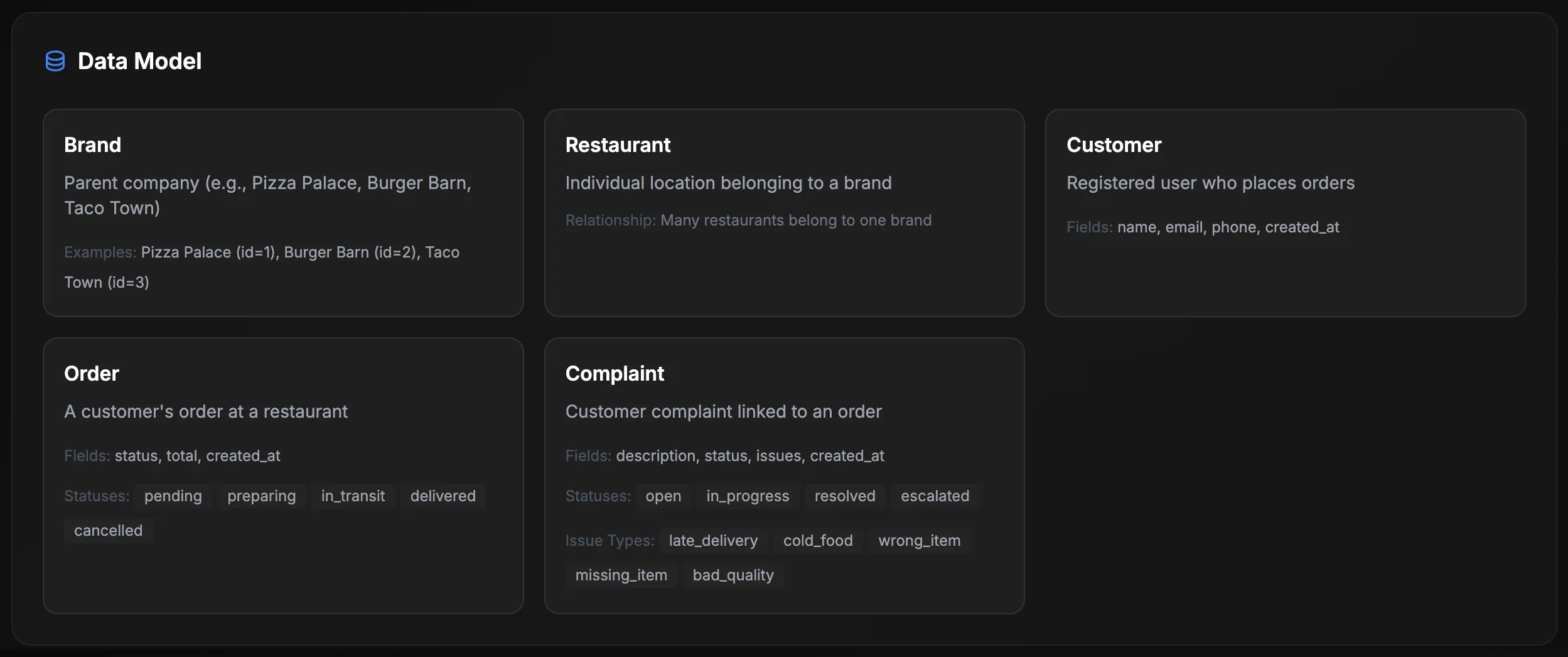

The data model has clear entities and relationships:

Brands: Pizza Palace, Burger Barn, Taco Town. Each with their own restaurants and menus.

Orders move through statuses: pending → preparing → in_transit → delivered (or cancelled).

Complaints have issue types: late_delivery, cold_food, wrong_item, missing_item, bad_quality.

This gives the agent realistic data to query and actions to take.

The API

The agent never touches the database directly. Instead, a FastAPI layer exposes what the agent is allowed to do:

Agent → API → Database⚠️ LLMs can hallucinate. If you let an agent write raw SQL, it may eventually generate something dangerous.

The API validates every request. Parameterized queries prevent injection. The agent can only do what the API explicitly allows.

Key endpoints:

| Route | Purpose |

|---|---|

GET /customers/{id} | Get customer info |

GET /customers/{id}/orders | Get customer’s orders |

GET /customers/{id}/complaints | Get customer’s complaints |

GET /orders/{id} | Get order with line items |

PATCH /orders/{id}/status | Update order status |

POST /complaints | Create a complaint |

PATCH /complaints/{id}/status | Update complaint status |

GET /brands/{id}/summary | Get brand stats (complaint rate, breakdown) |

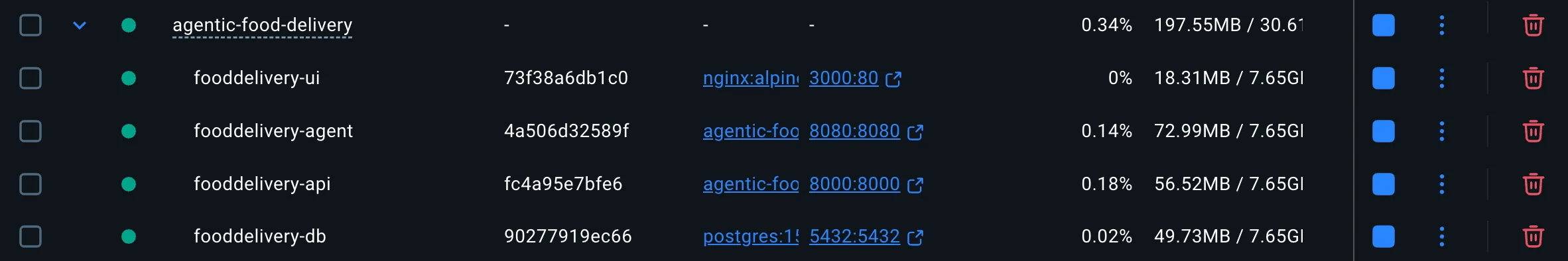

Docker Composition

Containerizing the system means we can clone the repo and run everything with a single docker-compose up:

services: db: image: postgres:16 # Database with seed data

api: build: ./api # FastAPI layer - the agent's interface to data

agent: build: ./agent # LangGraph agent with tools

vectordb: build: ./vectordb # ChromaDB for RAG (policy lookup)

ui: build: ./ui # Vue 3 chat interfaceOne docker-compose up and you’re running.

💡 You don’t need to understand every container to follow along. The database, API, and vector store are foundation layers. The interesting part is the agent itself.

An Agent Set Up for Success

We enhance our agent by providing it with tools. The agent has 15 tools, split between read and write operations:

Read Tools (11)

@tooldef get_customer(customer_id: int) -> dict: """Get customer information by ID.""" return _make_request("GET", f"/customers/{customer_id}")

@tooldef get_customer_orders( customer_id: int, status: Optional[str] = None, limit: int = 10) -> dict: """Get orders for a specific customer.

Args: customer_id: The customer's ID status: Filter by status (pending, preparing, in_transit, delivered, cancelled) limit: Maximum results to return """ params = {"limit": limit} if status: params["status"] = status return _make_request("GET", f"/customers/{customer_id}/orders", params)

@tooldef get_brand_summary(brand_id: int) -> dict: """Get summary statistics for a brand including complaint rates.""" return _make_request("GET", f"/brands/{brand_id}/summary")Other read tools: get_customer_complaints, get_customer_summary, get_order, get_order_complaints, get_complaints, get_complaint_stats, get_brands, get_restaurants.

Write Tools (4)

@tooldef create_complaint(order_id: int, description: str) -> dict: """Create a new complaint for an order.

Args: order_id: The order to file a complaint against description: Description of the issue """ return _make_request("POST", "/complaints", json={ "order_id": order_id, "description": description })

@tooldef update_order_status(order_id: int, status: str) -> dict: """Update an order's status.

Args: order_id: The order to update status: New status (pending, preparing, in_transit, delivered, cancelled) """ return _make_request("PATCH", f"/orders/{order_id}/status", json={ "status": status })Other write tools: add_complaint_issue, update_complaint_status.

The type hints (int, Optional[str]) tell the LLM what types to use. The docstrings explain valid values. This grounding prevents the agent from inventing parameters.

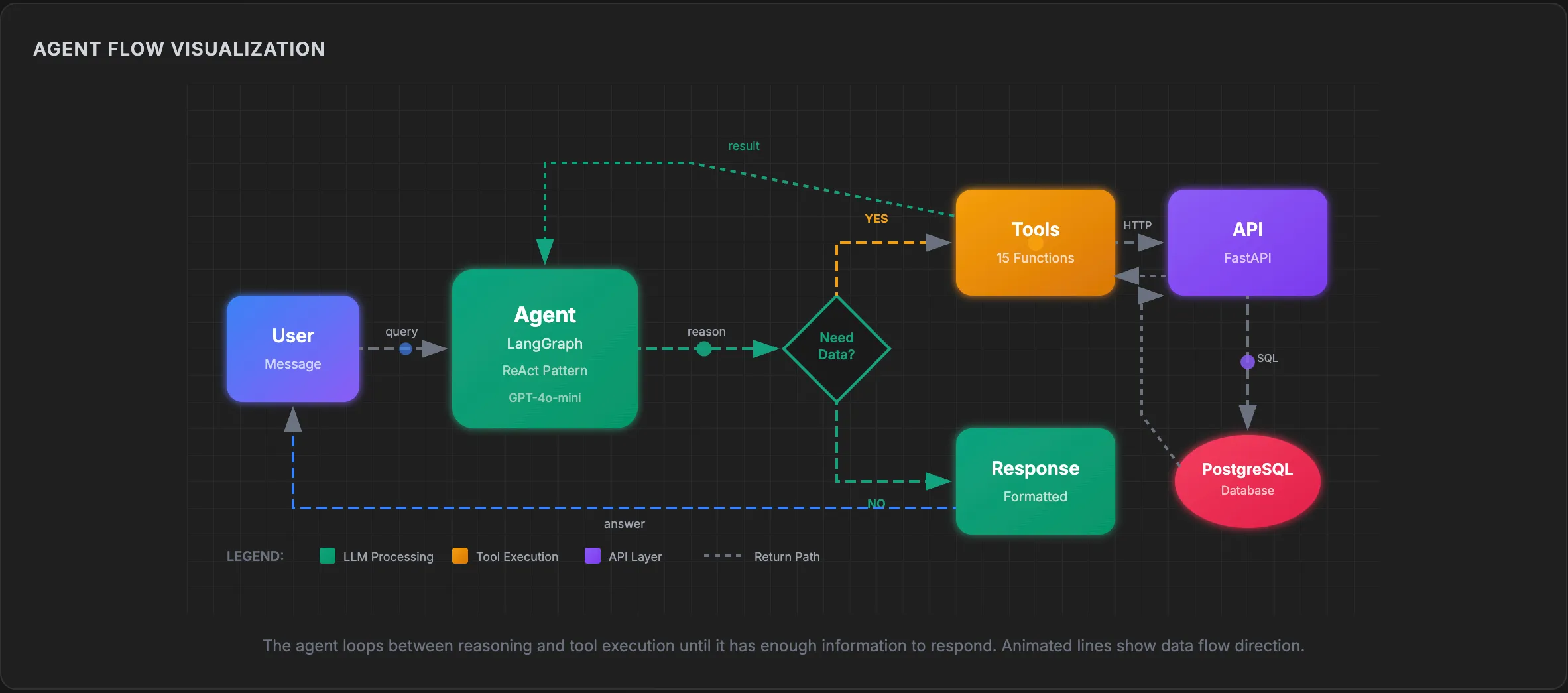

The Application Flow

The flow follows the ReAct pattern (Reasoning + Acting):

The agent loops until it has enough information to respond. A single user question might trigger multiple tool calls:

Example: “Compare complaint rates across all brands”

- Agent calls

get_brands()→ returns brand IDs [1, 2, 3] - Agent calls

get_brand_summary(1),get_brand_summary(2),get_brand_summary(3) - Agent formats results as a comparison table

- Agent responds to user

Implementing the Agent

The agent uses LangGraph, a library that makes the control flow explicit. You define nodes (agent, tools) and edges (what connects to what).

The State

First, define what the agent keeps track of:

from langgraph.graph import MessagesState

class AgentState(MessagesState): """State is just the message history.""" passThe Graph

from langgraph.graph import StateGraph, START, ENDfrom langgraph.prebuilt import ToolNodefrom langchain_openai import ChatOpenAI

def create_agent(): # Initialize LLM with tools llm = ChatOpenAI(model="gpt-4o-mini", temperature=0) llm_with_tools = llm.bind_tools(ALL_TOOLS)

def agent_node(state: AgentState) -> AgentState: """The agent decides what to do next.""" response = llm_with_tools.invoke(state["messages"]) return {"messages": [response]}

def should_continue(state: AgentState) -> str: """Route to tools or end.""" last_message = state["messages"][-1] if hasattr(last_message, "tool_calls") and last_message.tool_calls: return "tools" return END

# Build the graph graph = StateGraph(AgentState) graph.add_node("agent", agent_node) graph.add_node("tools", ToolNode(ALL_TOOLS))

# Define edges graph.add_edge(START, "agent") graph.add_conditional_edges("agent", should_continue) graph.add_edge("tools", "agent")

return graph.compile()That’s the core loop. The agent:

- Receives messages

- Decides if it needs tools

- If yes, calls tools and loops back

- If no, returns the response

Session Management

Real applications need to track conversations:

MAX_MESSAGES_PER_SESSION = 20SESSION_TIMEOUT_MINUTES = 30

sessions: dict[str, dict] = {}

def get_or_create_session(session_id: Optional[str]) -> tuple[str, list]: if session_id and session_id in sessions: session = sessions[session_id] session["last_accessed"] = datetime.now() return session_id, session["messages"]

new_id = str(uuid.uuid4()) sessions[new_id] = { "messages": [], "last_accessed": datetime.now() } return new_id, []Context windows are finite. Keep a sliding window of recent messages and expire inactive sessions.

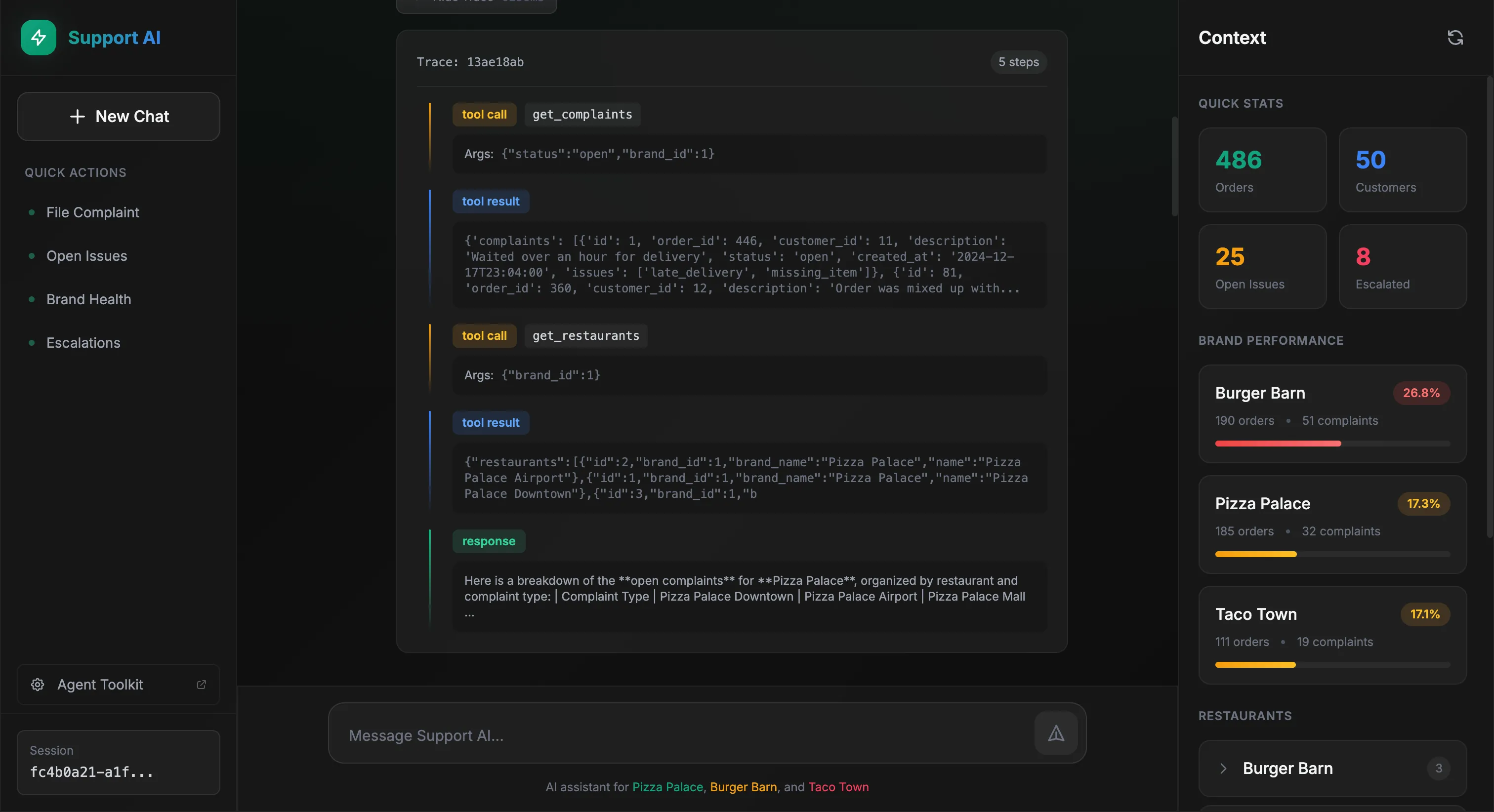

Observability

Every agent decision gets traced:

trace_steps.append({ "step_number": step_number, "step_type": "tool_call", "timestamp": timestamp, "content": { "tool_name": tool_call.get("name"), "tool_args": tool_call.get("args"), }})When something goes wrong, you can see exactly what the agent did and why.

📌 In production, observability is essential.

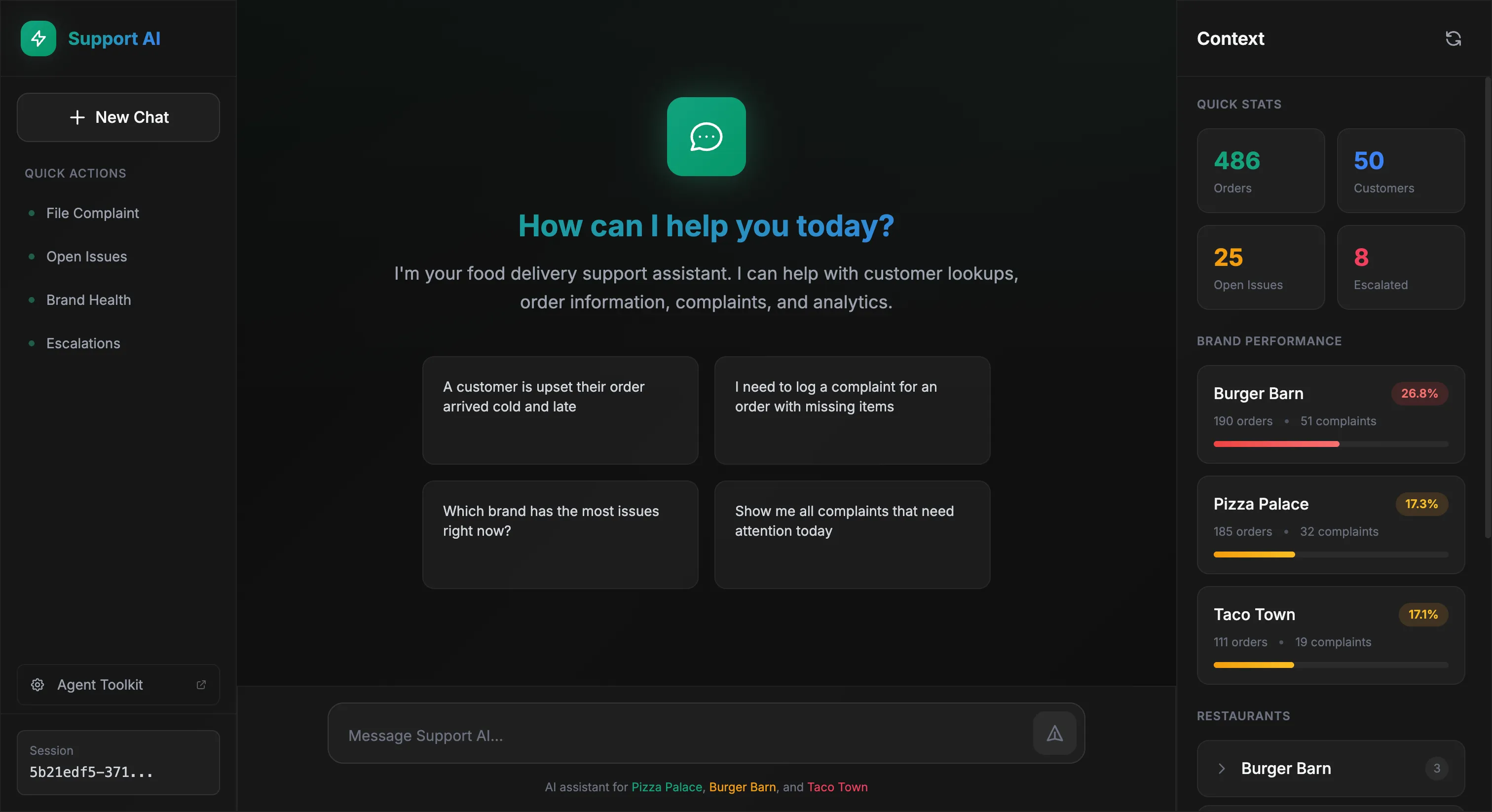

Seeing It in Action

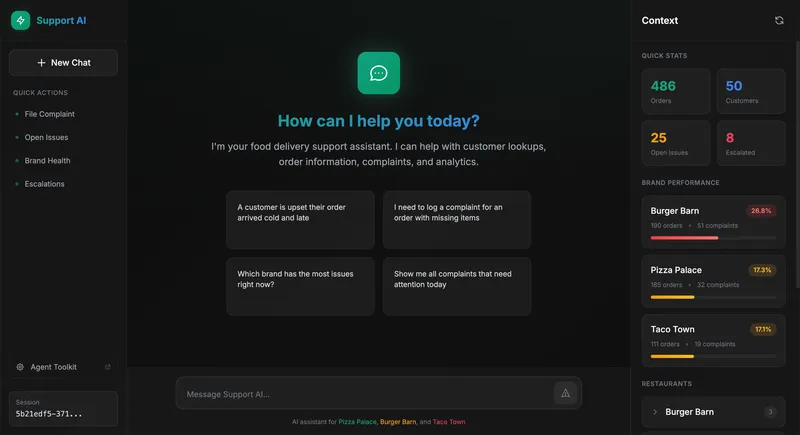

The chat interface shows a conversation area with a context panel displaying live stats and brand performance. Behind the scenes, the agent orchestrates the data.

📦 Try it yourself — Clone the repo and run

docker-compose up.

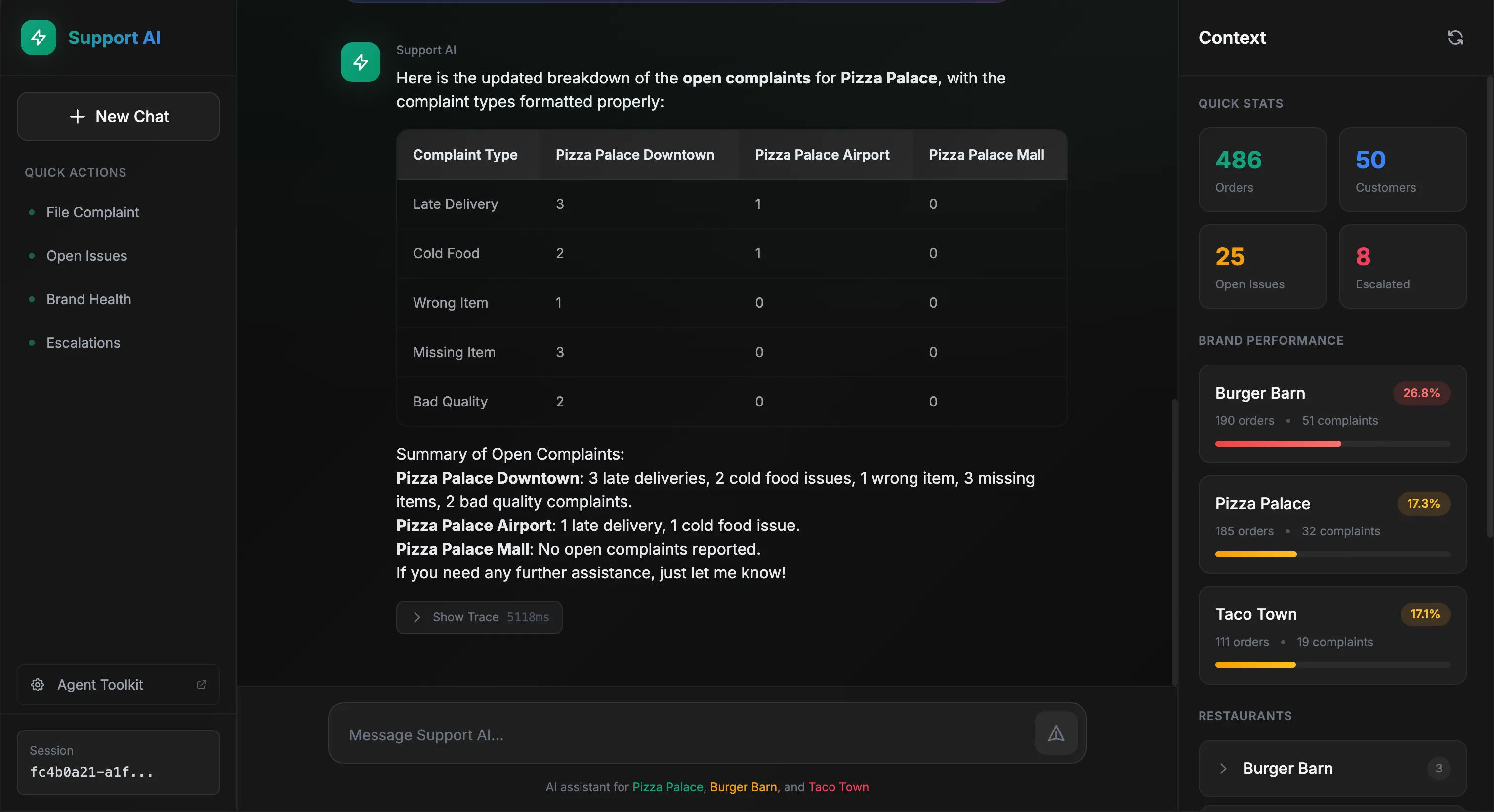

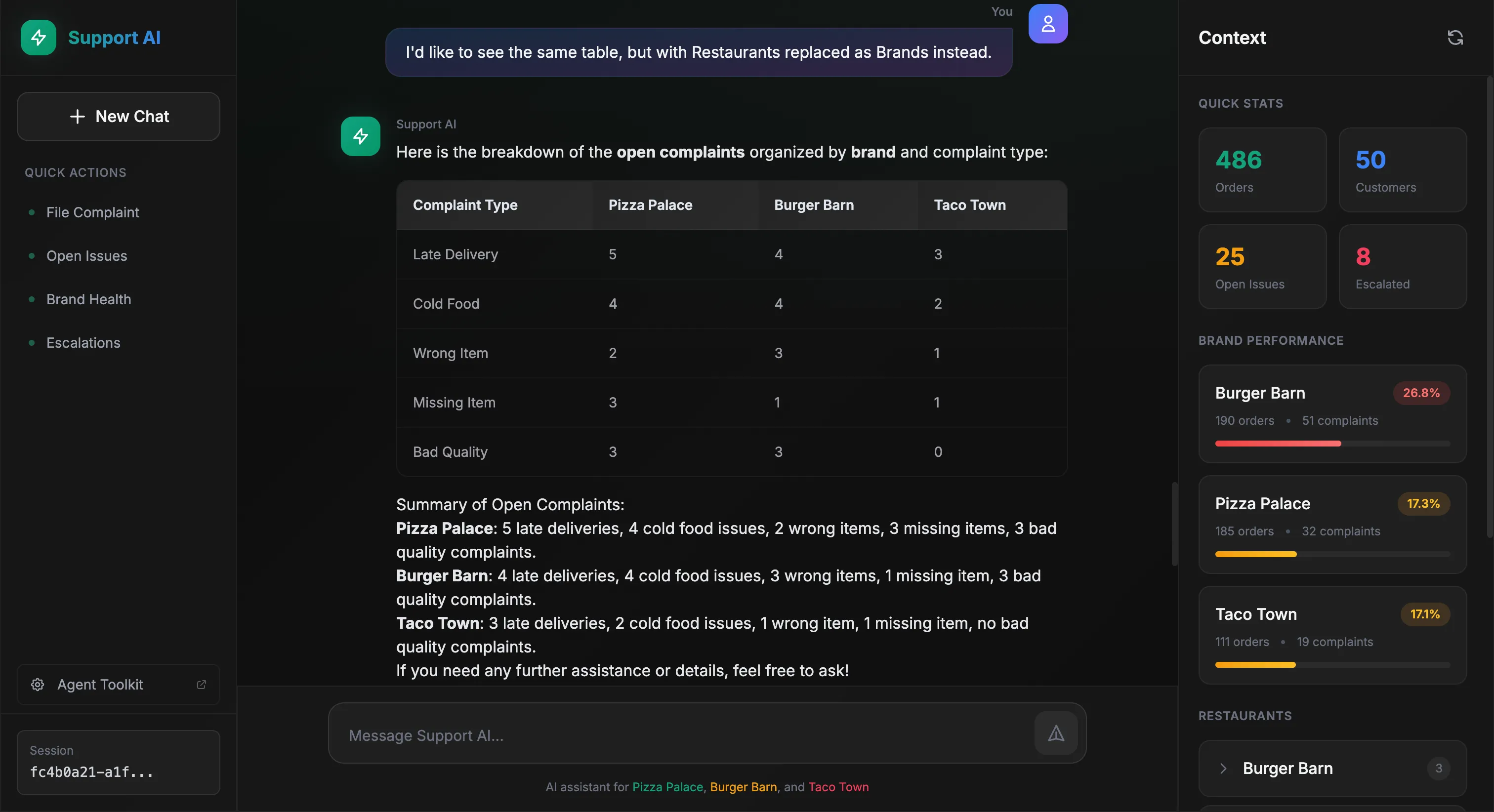

Let’s see the agent handle a real scenario. A Pizza Palace manager wants to see open complaints broken down by restaurant and issue type:

The agent queries the data and formats a table:

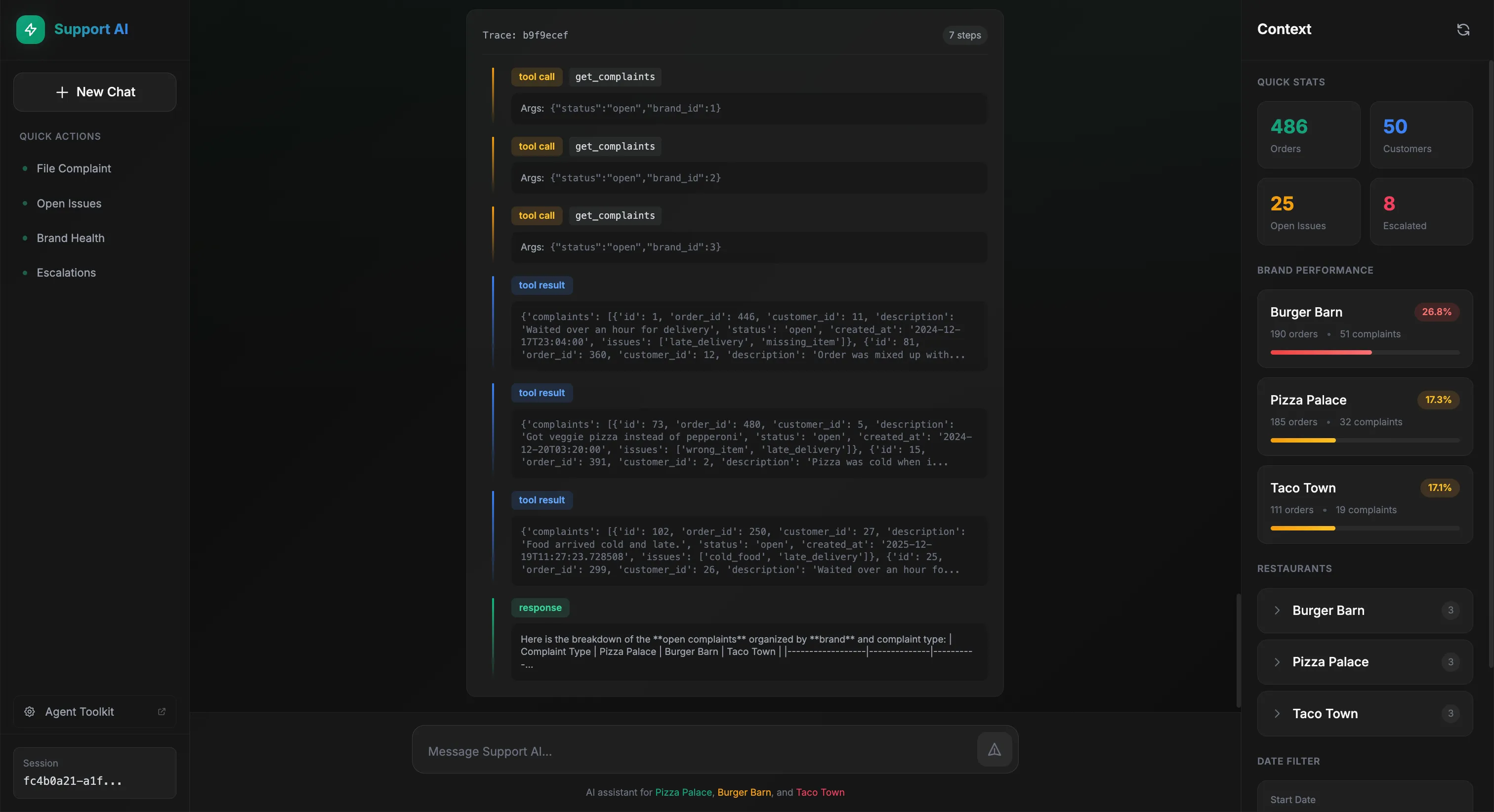

Behind the scenes, we can see exactly what tools the agent called:

The agent reasoned that it needed complaint data filtered by brand, called get_complaints with the appropriate filters, then get_restaurants to map restaurant IDs to readable names. Finally, it formatted everything into a table.

Now the user asks a follow-up, same table but by brand instead of restaurant:

The agent remembers the context and adapts:

This time, the agent called get_complaints three times, once for each brand, to gather the data needed for comparison. Same pattern, different scope.

Takeaways

Sprinkling AI into your product is easier than ever. So what’s the differentiator? The same engineering principles that have held strong for decades.

Getting started is easy. Getting to production is not.

Here are some best practices to keep in mind when implementing an AI agent:

Your domain should enable your agent. Slapping AI on a product and calling it a day rarely works. If your data model and APIs don’t give the agent the right context, it will always fall short. Structure your domain so your AI ambitions can succeed.

If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it. Evals and error analysis are what separate teams that ship from teams that don’t. Same principle as unit testing and observability in traditional software engineering.

Know what you want. Break down tasks. Avoid complex runtime decisions. Provide examples. Aim for single responsibility. SOLID principles apply to agents too.

Modularity. Design agents like you’d design a backend service. Swap out tools or models without tearing everything apart. Bounded contexts. Clear interfaces.

Think beyond accuracy. Don’t tunnel-vision on model performance. Latency, costs, and observability matter from day one. Work that never ships is work wasted.

Wrapping Up

These tools are exciting, but what will set you apart is the underlying engineering principles that have stood strong for years: separation of concerns, modularity, observability, testing.

The tools are new. The principles aren’t.

I hope this gives you a clearer picture of how to put it all together. For more on the fundamentals, Andrew Ng’s Agentic AI course on DeepLearning.AI is worth checking out.

Need help building this into your product? Let’s talk.

Want more content like this? Follow me on LinkedIn.