AI coding agents are becoming the norm. But with everyone having access to the same models, what’s the differentiator? It’s how we use them.

After coining the term Vibe Coding in early 2025, Andrej Karpathy recently introduced a new term: Agentic Engineering. The shift is from passively accepting AI output to actively orchestrating agents with structure, oversight, and intent.

It’s a similar shift to going from a developer’s mindset to an engineer’s mindset. From task-oriented to solution-oriented, from following instructions to challenging them.

But how do you actually make that shift? How do you go from vibe coding to agentic engineering?

Let’s look at what that shift might look like.

Same Productivity Problem in a Trench Coat

How do we enhance the way our agents write code and build solutions?

Replace “agents” with “engineers” and you’ll see we’ve been asking this for decades. And the answer has always been the same: better codebases, better processes, better context.

The Engineer

Think about what we need to build things well:

- A clear problem statement. What are we solving? Why? How?

- Domain understanding. What am I working with?

- Clarity of outcome. How do I know when I’m done?

Now think about the opposite. The engineering nightmare:

- A codebase with little to no documentation

- No one on the team knows how the system works or why it was built this way

- No understanding of why this solution even exists

- No clear requirements. No consensus on what done looks like.

- Everyone afraid to touch anything because it all hangs by a thread

We tend to blame this on “legacy codebases,” but age isn’t the problem. A 20-year-old, well-maintained project can still stand strong while your 20-day-old vibe-coded app becomes a spaghetti mess faster than you can get your first client.

The problem isn’t age. It’s a lack of standards, structure, and context.

The Team

As engineers, we don’t work alone. Collaboration is essential.

A productive team has shared conventions and documented architecture. There’s a defined process for how work moves from idea to production. Code review. QA. Deployment gates. No single person holds all the context. Responsibility is distributed, delegated.

When that system breaks down, it doesn’t matter how talented the individuals are. Work gets duplicated. Reviews get skipped. Knowledge lives in one person’s head, and when they go on vacation, everything stalls. We’ve all been there.

The Agent

So how does this map to our AI coding agents?

Agents can digest large amounts of information quickly. That’s their edge. But they lack human intuition. They can’t infer what isn’t there.

An individual agent needs the same things an engineer does: context about the codebase, clear requirements, a defined outcome. Without those, it guesses. And it guesses confidently.

A team of agents needs the same things an engineering team does: coordination, defined roles, quality gates. Without those, multiple agents will duplicate work, contradict each other, and produce inconsistent results.

If we want our agents to do better work, we need to give them what we’d give any engineer joining our team.

Outsource Labor, Not Thinking

AI coding agents become more impressive and capable by the day, affecting the way we work at a core level. As we go through this transition, we have to ask ourselves: where is the human in the loop?

Following the theme of enhancement instead of replacement, let’s identify how we can leverage these tools to build things that matter more efficiently. My suggestion: outsource labor, not thinking.

The idea is to trade repetitive work for meaningful work. Spend less time typing and more time thinking about how to design solutions and improve the outcome.

Most of us now find ourselves in a manager-like position where we need to provide proper guidance to the actors who build the things we envision. And there’s another reason to keep the thinking part to ourselves:

What you don’t use, you lose.

We should use agents to move faster through the work that doesn’t require constant judgment. And stay involved in the parts that do.

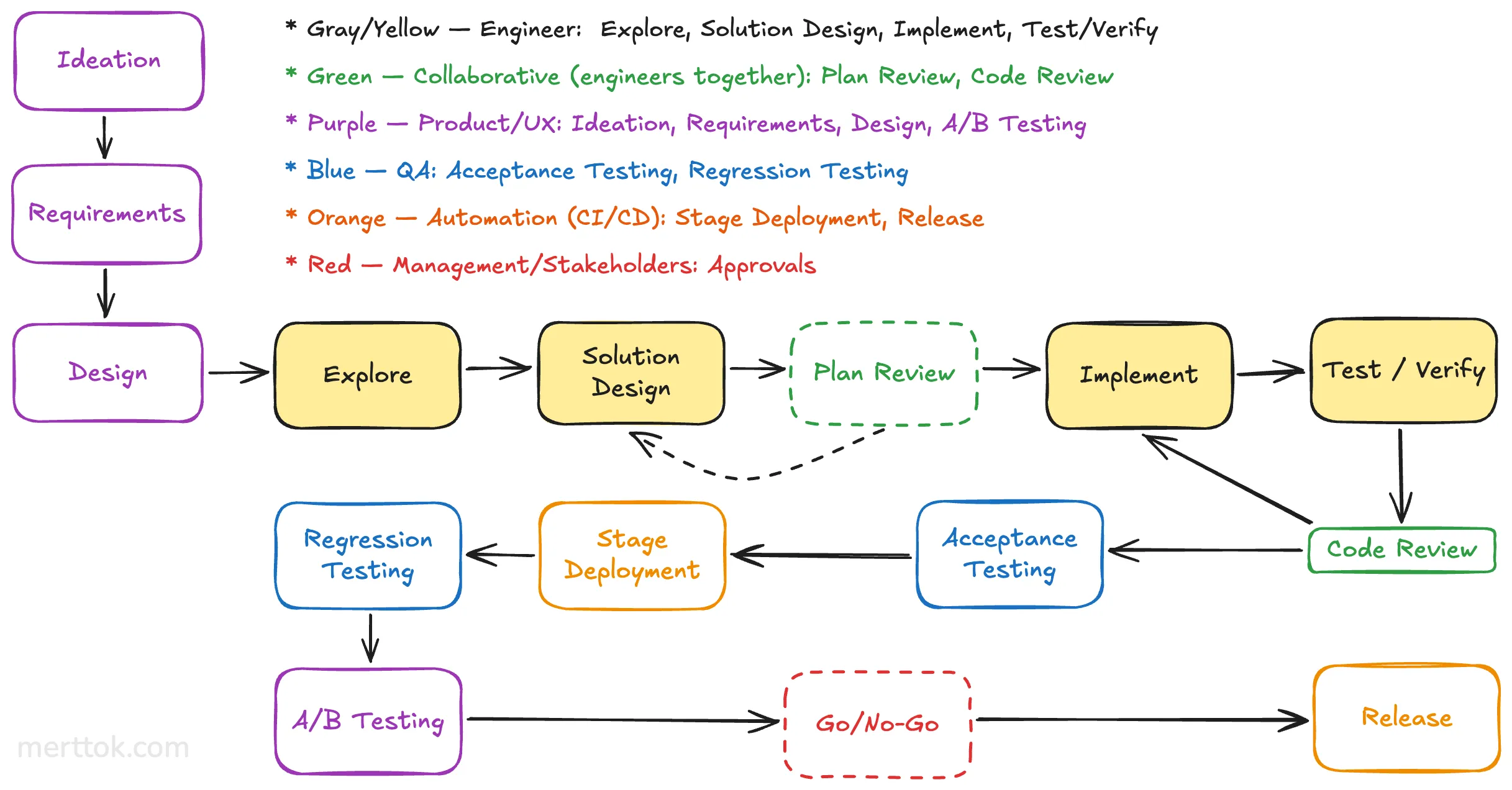

The Flow

To improve the process, we first need to understand it. So let’s take a look at what an average software development cycle might look like, from an engineering team’s perspective.

This has been refined over decades. Different teams tweak it, but the shape is universal: understand the problem, design a solution, validate it, build it, verify it, ship it.

Now let’s break this down. At every step, three things are at play:

- What. The task. What needs to happen at this step.

- Who. The actor. Who is responsible for doing it.

- How. The method. What rules, tools, and standards govern how it gets done.

Think about any step in that flow. There’s always a task to complete, someone responsible for it, and a set of rules around how it gets done. We’ve spent decades figuring this out.

You’re the Manager Now

If agents are doing what engineers do, and teams of agents are doing what engineering teams do, then where does that leave us? We become the manager.

Let’s identify what we need to do to become good managers for our team of agents.

| Good manager | Bad manager | |

|---|---|---|

| The work | Grasps the problem, identifies blockers beforehand, decides the approach. | Passes the ticket along without reading it. |

| Context | Makes sure the team knows what they’re working with and why. | Assumes the team will figure it out. |

| Process | Defines the steps and the acceptance criteria. | ”Just make it work.” |

| People | Assigns the right people based on their strengths. | Gives everything to whoever’s available. |

| Rules | Sets permissions, quality standards, review process. | No standards. No review. Ship it. |

Now extend this to your agents. Context is a rules file. Process is a skill. People are agents. Rules are settings. Same principles, different actors.

Putting It into Practice

Let’s see how these ideas can be put into practice. I’ll be sharing my personal workflow for tasks that vary in complexity. The specific examples use Claude Code, but the underlying principles and concepts translate to all coding agents.

CLAUDE.md # The rules file. Always loaded..claude/ context/ architecture.md # System design, what talks to what patterns.md # Code conventions the agent should follow glossary.md # Domain terms and shared vocabulary dependencies.md # External services, APIs, databases testing.md # Test setup and conventions skills/ onboard/SKILL.md # Scans codebase, generates context files task/SKILL.md # Full feature workflow review/SKILL.md # PR review process bugfix/SKILL.md # Bug investigation and fix agents/ explorer.md # Read-only, gathers context organizer.md # Structures and refines documentation architect.md # Proposes solution designs builder.md # Write access to code, no git reviewer.md # Read-only, fresh-context code review settings.json # Permissions, hooks, MCP configdiscovery/ EX-421/ # One folder per task jira-ticket.md codebase-analysis.md implementation-plan.md PR-DESCRIPTION.mdHere are some example skills and agents you can configure to automate your engineering workflow. These are just examples. Build on them as you see fit.

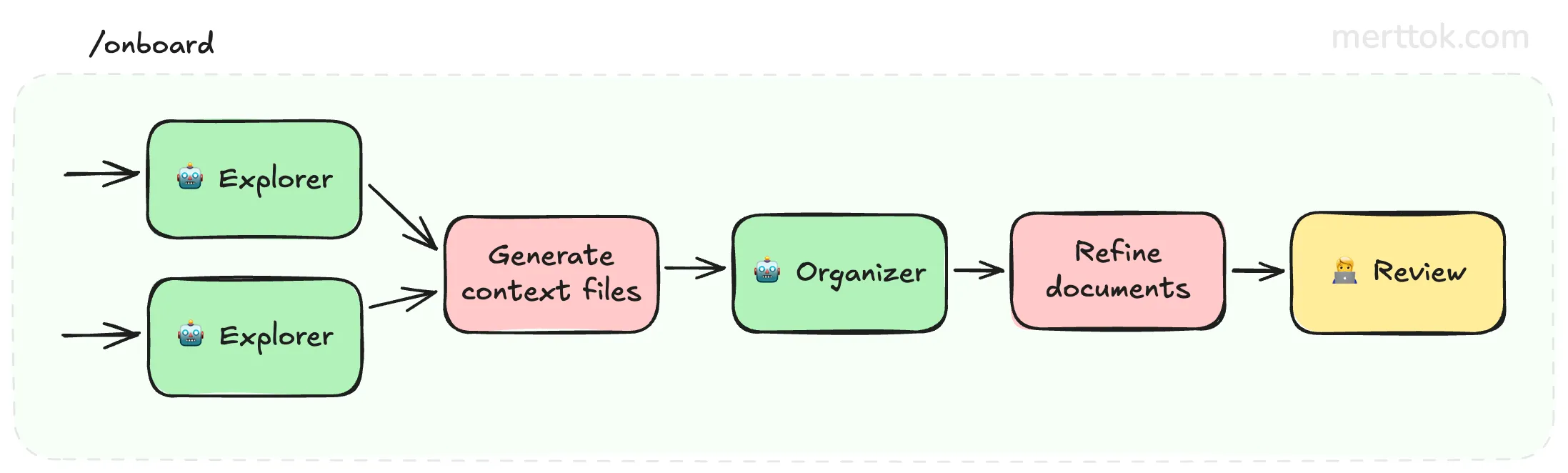

/onboard

Runs once per project. Explorer agents scan the codebase and an organizer structures their findings into context files. You review and refine. From that point on, every agent knows the codebase before you type a word.

Remember the flow from earlier? The idea is to map agents to each step. An explorer for discovery, an architect for planning, builders for implementation, a reviewer for code review. Each step in the flow gets an actor with the right scope and permissions.

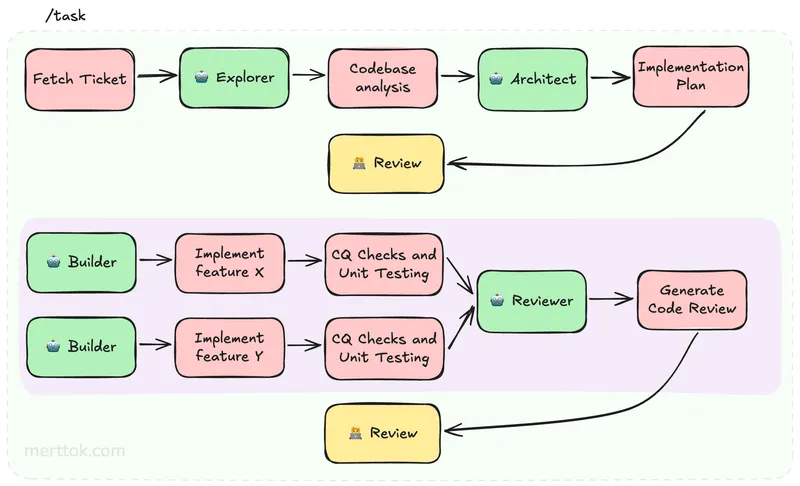

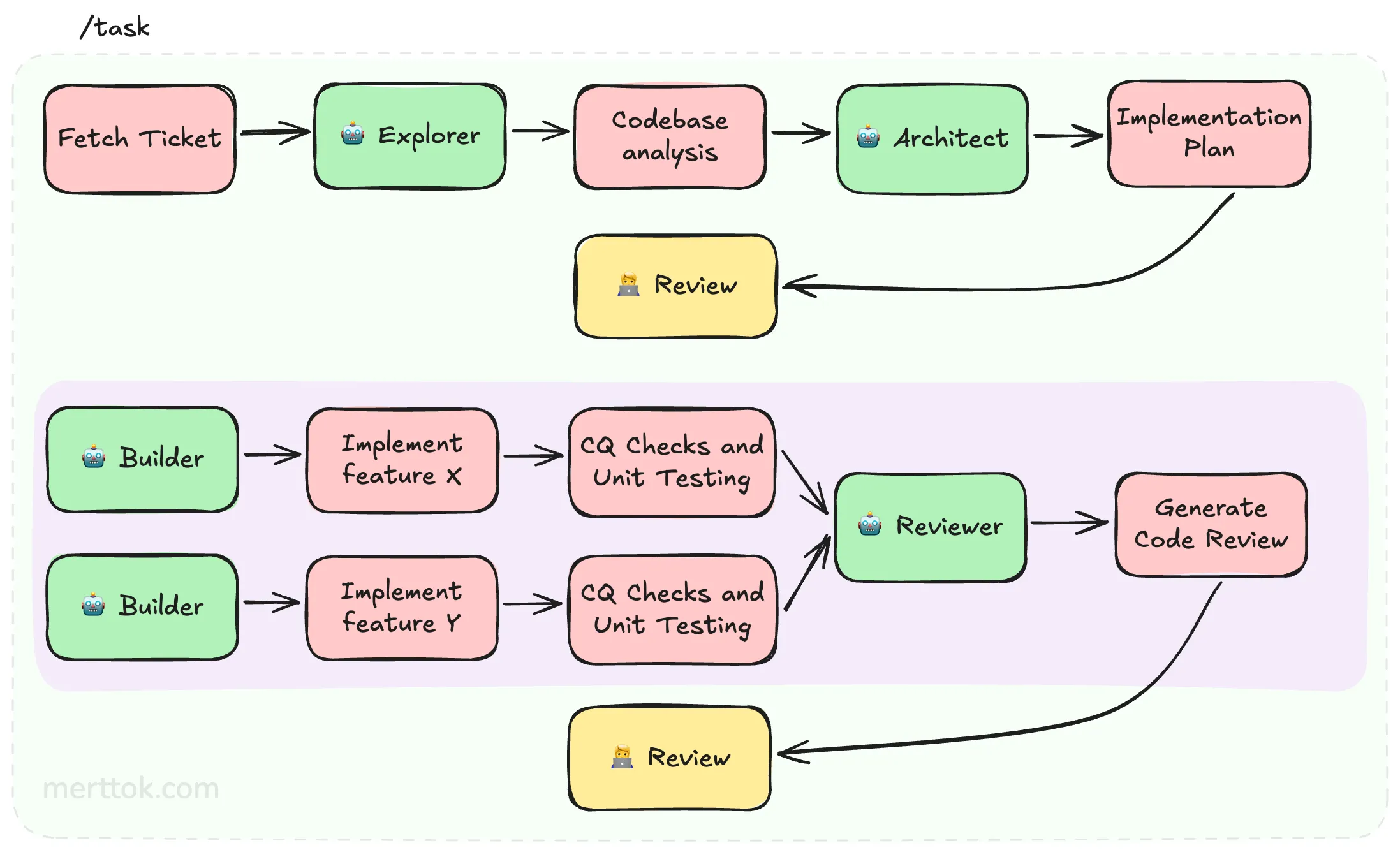

/task

You read the ticket, decide the approach, run /task EX-421. The skill pulls the ticket via MCP, the explorer digs into the relevant code, and the architect proposes a plan. You review it.

Once approved, builders work in parallel on separate git worktrees. Hooks handle formatting, linting, and tests after every edit. A reviewer agent with fresh context gets the code last. You review the diff, merge, and commit.

The discovery folder keeps all of this durable. One folder per task with analysis, plans, and decisions that survive across sessions.

| Vibe Coding | Agentic Engineering |

|---|---|

| The agent rediscovers the codebase every session | /onboard generates context files once. Every agent reads them from that point on. |

| ”Add bulk export to reports. The codebase uses Express with a service layer…” | /task EX-421. The ticket, context, and patterns are already available. |

| ”Review the code you just wrote” | Reviewer agent triggered automatically. Fresh context, no sunk cost. |

| Context is lost post-compaction | Discovery folder preserves progress across sessions |

| ”Remember to run the linter” | Hooks run formatting and tests after every edit |

This example focuses on the engineering steps, but the same idea extends to design, product, and CI/CD. The flow is yours to define.

Takeaways

Same problem, different actors. What makes engineers productive is what makes agents productive: context, process, guardrails, and clear expectations.

Outsource labor, not thinking. Let agents handle the repetitive work. Keep the architectural decisions, trade-offs, and judgment calls to yourself. What you don’t use, you lose. Keep your thinking sharp.

Be in the driver’s seat. Approach your agentic pipeline like a manager would. Define the What, Who, and How. Skills define the process. Agents fill the roles. Settings enforce the rules.

Learn your tool well. Hooks, skills, agents, MCP, permissions. Most coding assistants offer more than you think. Learn what features are available in your toolkit.

Wrapping Up

The shift from vibe coding to agentic engineering isn’t about the tools. It’s about how we think about the work. The engineers who build systems around their agents will outpace those who just prompt and hope.

Want help setting this up for your team? Let’s talk.

Want more content like this? Follow me on LinkedIn.